The Two Questions I’d Ask Bill Gates

Gates’ trust in government and oversized belief in himself are a problem for us all

Gates’ trust in government and oversized belief in himself are a problem for us all

Listen to a reading of this article:

The phone rings, waking me from a melancholic dream of disinherited dinosaurs and their endless search for their wealthy uncle, Waldo.

“Mr. Winchell?” comes a disembodied, tinny voice belonging to someone who I simply know as The Editor.

“Yup.”

“We’ve got somethin’ for ya. A, uh, big fish, one of the biggest in the pond.”

“Bozo Bezos?”

“Nah, I didn’t say the biggest.”

“Ewan McGregor?”

“Why would you stoop so low?” The Editor asks.

“Ewan’s all right,” I answer. “He did his best in season 3 of Fargo.”

“Never mind,” The Editor says. “We did it.”

“Spit it out, already, I wanna see if I can help those dinos find Waldo.”

“Waldo?”

“Now you never mind. Who is it?”

“Gates.”

“Fuck off,” I say, about to hang up because The Editor’s got a bad habit of waking me for no other reason other than to prove his prowess in chain yanking.

“This is legit,” The Editor says. “But he said only two questions and ya gotta do it on Microsoft Teams in five.”

I hate Microsoft Teams, but I submit.

Bill Gates doesn’t know what he’s signed up for and my monthly check to The Editor is already in the mail.

Two questions. Which two questions would you ask Bill Gates if The Editor gave you this chance?

Question #1

I keep my niceties to a simple “Hello, Mr. Gates” and then I pop the first one: “What do you think about the JFK assassination?”

“I thought you wanted to ask me about vaccines,” Gates whines.

God, the way he says vaccines makes his voice screech across my mind like Edward Scissorhands with a chalkboard.

“I was told two questions, no restrictions, ask whatever I want,” I say.

“Sure, sure,” Gates says, tugging at a wedding ring that no longer exists. “JFK? What about it?”

“You’re not tricking me,” I say, holding my second question tight. “Answer the question.”

“I mean, I don’t know,” Gates starts, “I guess I never put much thought into it.”

“Figured as much,” I say.

Did I waste that question? Maybe. But hold your judgment until after question number two, okay?

Question #2

“My second question is — ”

“That’s it?” Gates says. “No follow-up?”

“No,” I say. “I believe you. You were making computers, taking over the world. I get it.”

Gates smiles. He thinks I’ve just paid him a compliment. Let him think that.

“So, the second question is — “ Gates is still smiling — “Have you done any shadow work?”

“What’s that?” Gates asks.

“You know, digging into your unconscious to see how it drives your behaviors so that you can live more consciously,” I say.

“I’d rather talk about vaccines,” Gates says.

“Thanks for answering my questions,” I say and, just like that, Gates is gone.

Yeah, yeah, I know, you think I blew it. Of all the questions to ask one of the most powerful people in the world during a global crisis that he’s played an oversized part in, I asked him about his fucking shadow.

Now you’re convinced you know why I quit journalism before the age of 30, right?

I think you should let me explain before you make that judgment and then you can have at it.

Why Did I Ask Him Question #1?

To answer why I would ask for Gates’ thoughts about the JFK assassination I’m going to ask you to suffer through, in full, the section in Gates’ recent blog post about disinformation. I know it’s a long pull quote, but I don’t want there to be any accusations that I took what he said out of context. Here is what he wrote:

“The other area where there is huge room for improvement is in finding ways to combat disinformation. As I mentioned, I thought demand for vaccines would be way higher than it has been in places like the United States. It’s clear that disinformation (including conspiracy theories that unfortunately involve me) is having a substantial impact on people’s willingness to get vaccinated. This is part of a larger trend toward distrust in institutions, and it’s one of the issues I’m most worried about heading into 2022.

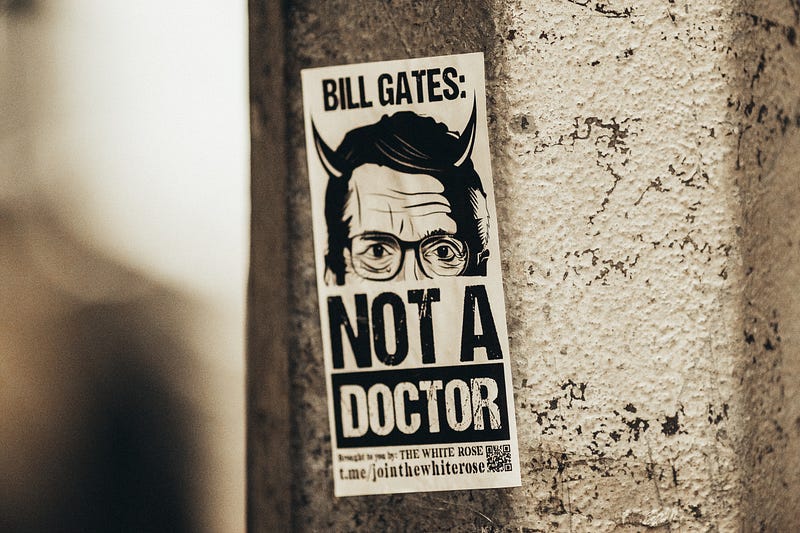

Let me pause him there. Notice Gates’ hubris in his “clarity” that it’s disinformation that explains why people are not willing to get vaccinated for COVID-19. And notice how that hubris caused him to widely misunderstand the public’s mind and thus overestimate the likelihood that his pet project of getting everyone vaccinated would happen.

Okay, back to it (and I promise not to interrupt every paragraph!).

The pandemic has been a massive test of governance. When the pandemic finally comes to an end, it will be a tribute to the power of global cooperation and innovation. At the same time, this era has shown us how declining trust in public institutions is creating tangible problems and complicating our efforts to respond to challenges. Based on what I’ve seen over the last couple of years, I’m more worried than I’ve ever been about the ability of governments to get big things done.

Not to worry, Bill — because you’ve got a superhero cape! Oops, I promised. Sorry…

We need governments to take action if we’re going to make progress on challenges like avoiding a climate disaster or preventing the next pandemic. But declining trust makes it harder for them to be effective. If your people don’t trust you, they’re not going to support major new initiatives. And when a major crisis emerges, they’re less likely to follow guidance necessary to weather the storm.

This decline in trust is happening all over the world. The 2021 Edelman Trust Index shows worrying drops across the globe. Part of it is understandable: Any time you have a really big crisis like a pandemic, people look for someone to blame. Governments are an obvious target.

But this trend toward less trust in government didn’t start in 2020. The pandemic only made clearer what had already been happening.

We’re about to get to the good part, where we learn how Gates ties the JFK assassination into his understanding … or not. But seriously, pay extra attention here.

So, who or what is to blame? It’s clear that increased polarization is a significant driver. This is especially evident here in the United States, although we’re far from alone. Americans are becoming more divided and more deeply entrenched in their political beliefs. The gap between the left and the right is becoming a gulf that’s harder and harder to bridge.

There are many reasons for this growing divide, including a 24-hour news cycle, a political climate that rewards headline generation over substantive debate, and the rise of social media. I’m especially interested in understanding the latter, since it’s the most technologically driven.

I believe that governments need to regulate what you can and can’t use social media for. In the United States, this topic has raised a lot of free speech questions. But the reality is that our government already has all sorts of norms around communication.

You can’t slander someone or trick them out of their money by promising something you don’t deliver on.

Umm, really? Isn’t that the name of the game in advertising? Beer ads using sexy models imply beer equals sex with models, right?

Network TV shows can’t show explicit sex scenes or use certain profane language before 10 p.m. in case children are watching. These rules exist to protect people. So why couldn’t our government create new rules to protect them from the most tangible harms created by social media? They wouldn’t be easy to enforce, and we’d need public debate about exactly where the lines should be, but this is doable and really important to get done. A video falsely claiming that the COVID-19 vaccine makes you infertile should not be allowed to spread widely under the guise of being news.

Since we’re spitballing here about what information was widely spread under the guise of being news, how about stopping the tweet of a famous Sesame Street character convincing small children to take a risky medical intervention that is promoted as “safe and effective” when we have no way of knowing the long-term impacts of that intervention and which, at best, gives them about six months protection against a disease that poses little threat to them?

As people become more polarized on both sides of the aisle, politicians are incentivized to take increasingly extreme positions. In the past, if you didn’t like the way a government agency was operating, you’d run on a platform of fixing it. Today, we’re seeing more people get elected on the promise of abandoning institutions and norms outright.

When your government leaders are the ones telling you not to trust government, who are you supposed to believe? This creates a compounding effect where people lose confidence in government, elect politicians who share their distrust, and then become even more disillusioned as their leaders tell them how bad the institutions they now run are.

This is usually where I’d lay out my ideas for how we fix the problem. The truth is, I don’t have the answers. I plan to keep seeking out and reading others’ ideas, especially from young people. I’m hopeful that the generations who grew up online will have fresh ideas about how to tackle a problem that is so deeply rooted in the Internet.

This problem requires more than just innovation to solve, although there are some steps we can take (especially around e-governance and making data more available to the public) to make modest improvements. There are all sorts of ways that great scientific ideas get published and tested. For great political ideas, the pathways are not as clear. Thinktanks and academics can point in the right direction, but at the end of the day — in a democracy at least — it seems to me like you need to pick the right leaders and give them the space to try new ideas.

First, Gates got one thing right: There is increasing distrust in public institutions. The problem is where he attributes the cause of this distrust to. He says it’s the result of political polarization which has “many reasons” and then he lists three of them: “a 24-hour news cycle, a political climate that rewards headline generation over substantive debate, and the rise of social media.”

He really zeros in on that last one when, a few paragraphs later, he writes about “a problem that is so deeply rooted in the Internet.”

Do you see what he doesn’t point his finger at? I see one thing: The public institutions themselves.

Which is precisely why I want to ask him what his thoughts are about the JFK assassination. Because the JFK assassination — and the cover-up that followed — was a foundational event in creating distrust in the modern American public. And that distrust was created by the government itself — with some serious assists from major, traditional media outlets such as the New York Times and CBS (and remember, this was well before the 24-hour news cycle).

Gallup has taken regular polls over the years since Kennedy was killed and in all but one (1966), the majority of Americans haven’t believed the Warren Commission report’s findings that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. Interestingly, even when a poll was taken in the week after the shooting, the majority (52 percent) felt that “others were involved in a conspiracy” and only 29 percent thought Oswald acted alone.

This single event, and the Warren Commission’s report, has had a lasting impact on America’s ability to trust its government.

I was born in 1973, so I wasn’t here on that fateful November day in 1963. However, I grew up just assuming there was a conspiracy to kill Kennedy. Then, when I was 19 years old, I had that feeling reinforced when I watched Oliver Stone’s JFK, a fictional account of a real-life New Orleans attorney named Jim Garrison who investigated into what really happened that day.

There were many things Stone didn’t know when he made that movie and over the years more files have been released about the assassination, giving us more clues, so Stone decided to re-visit the topic, this time with a documentary that came out this fall titled, JFK Re-Visited: Through The Looking Glass.

One of the most striking things about this fascinating documentary occurs in the opening 10 minutes when Stone shows how an otherwise normal day in peaceful early 1960s America was shattered and several shocked citizens are interviewed.

One of my favorite current thinkers, Charles Eisenstein, wrote a very thought-provoking essay this fall about the Kennedy assassination and in it, he wrote about how his father felt that November day was the day things turned dark in America.

Eisenstein writes, “My father, my country, and to some extent the world, has not yet fully come to terms with (Kennedy’s assassination). It is like a radioactive pellet lodged inside the body politic, generating an endlessly metastasizing cancer that no one has been able to trace to its source.”

Eisenstein goes on to point out how so much of conspiracy theory culture grew out of that event and he correctly doesn’t flat-out dismiss those theories.

Most of today’s older generation were in their youth on that tragic day. Bill Gates had just turned eight years old, too young to put much thought into whether the government was telling the truth at the time. But he grew up in those 1960s, that decade of assassinations of major political figures, reaching the age of 15 at decade’s end. And he came of age in the 1970s when the public skepticism toward the government was fueled by the Vietnam War, Watergate and then, in 1975, by revelations from the Church Committee, a U.S. Senate investigation into abuses by the CIA, FBI, IRS and NSA. That committee revealed many shady behaviors in the 1950s and 1960s by those agencies and is likely one of the reasons in 1976 that 81 percent of Americans believed there was a conspiracy to kill JFK versus only 11 percent who felt Oswald acted alone.

“Once you kill a president in broad daylight on the streets of an American city and everyone knows that powerful forces did it, that sends a signal not only to the American people but to the American media, to the American future leadership,” said David Talbot, author of Brothers: The Hidden History of the Kennedy Years, at the end of Stone’s documentary. “And if America really wants a democratic society then we should get to the bottom of this traumatic crime that continues to reverberate throughout American history.”

All that said, my guess about how Gates responded to JFK’s assassination is evident by the fake dialogue I created: he didn’t. He was focused on his work, a very American thing to do. If you re-read his blog post, you’ll see that not once does he even slightly suggest public institutions have earned our distrust.

Even worse is Gates’ attempt at offering a solution to the trust problem: “I believe that governments need to regulate what you can and can’t use social media for.”

See that? While he mentions the 24-hour news cycle as one of the three causes of the distrust, he doesn’t mention any action against traditional media. Instead, he focuses solely on what you can and can’t use social media for. You, as in the average Joe and Jill. He doesn’t dare suggest that people like him shouldn’t be able to donate hundreds of millions of dollars to major news organizations around the world, likely influencing their coverage (see link below). Nor does he question why he’s allowed to go onto said outlets to offer his opinions about how we should solve our problems.

Journalism's Gates keepers

Last August, NPR profiled a Harvard-led experiment to help low-income families find housing in wealthier neighborhoods…www.cjr.org

While I won’t deny that we all could use a lot more training in journalistic ethics now that social media has, in a sense, made us all journalists, to ignore the role that traditional media has played in spreading disinformation is naïve at best.

Kennedy Was A Lot Smarter Than Gates

Interestingly, President Kennedy gave a nuanced speech in 1962 to the American Newspapers Publishers Association where he was imploring journalists to, at times, work with the government “to prevent unauthorized disclosures to the enemy.” From my reading of the fascinating speech, Kennedy is trying to find a balance between respecting freedom of the press and having a press act with enough self-discipline to not reveal important information that may be used to harm the United States.

Notice, though, he is not suggesting what Gates does. Instead, he says to these journalists, “No governmental plan should impose its restraints against your will (emphasis mine), but I would be failing in my duty to the nation in considering all of the responsibilities that we now bear and all of the means at hand to meet those responsibilities, if I did not commend this problem to your attention and urge it’s thoughtful consideration.”

What you see in this comment is Kennedy respecting that the government and the media can be, at best, equals. Wouldn’t it be nice if people like Gates treated us the same and didn’t always suggest top-down solutions to problems?

Returning to Stone’s documentary, you’ll learn that mainstream media outlets were used by figures in government to spread the cover-up of the Kennedy assassination. I think most of us recognize that this trend of the government colluding with major media outlets to lie with justifications like “it’s for your protection” hasn’t stopped in our lifetime. Should the government be doing this?

You might disagree with me on the answer to that question. But I’d like to think you will agree that Gates’ focus on us as the problem without considering the government and mainstream media, and his suggestion that the solution is for that same government to control how we use social media are, at the very least, troubling.

Why Did I Ask Him Question #2?

Now, let’s get to question two, shall we? There are a few reasons I’d like to ask Bill Gates if he’s done any shadow work.

First, it’s an interesting question to ask anybody. If someone asked me, I’d answer, “Yes, but I’ve only just begun. In the past few years, I’ve done some guided meditation exercises with a life coach where I met aspects of my Shadow, I’ve engaged in some deep, daily journaling, and I’ve had conversations with various archetypes in my inner world where I let the Shadow participate freely without censor. Last, I’ve been taking in media to learn more about the concept of the Shadow and more things that I can do.”

One of the most important things one learns when studying the concept of the Shadow is that we tend to project our Shadow onto the external world and then fight it out there. This is the core of what drives the Savior archetype and, I think it goes without saying, a man like Bill Gates probably has a fair amount of Savior complex running his personal OS.

If you want to read about some of Gates’ very questionable behavior in acting out his Savior complex, look no further than the work of Indian environmental activist Vandana Shiva. Shiva has been on the frontlines battling against Gates’s technocratic, monopolistic vision of the world and has been one of the clearest and knowledgeable people speaking out against him.

In her book, Oneness versus the One Percent, she writes, “Health is about life and living systems. There is no ‘life’ in the paradigm of health that Bill Gates and his ilk are promoting and imposing on the entire world. Gates has created global alliances to impose top-down analysis and prescriptions for health problems. He gives money to define the problems, and then he uses his influence and money to impose the solutions. And in the process, he gets richer. His ‘funding’ results in an erasure of democracy and biodiversity, of nature and culture. His “philanthropy” is not just philanthrocapitalism. It is philanthroimperialism.”

Philanthroimperialist: A Better Title For Gates Than Philanthropist

Next time you see Gates interviewed with the “philanthropist” tag under his name, perhaps substitute it with “philanthroimperialist.”

Perhaps it’d be easier to rest on the topic of Gates if his ideas were good ones. But I suggest you read the rest of that excerpt from Shiva’s book before you assume that is the case. Also, consider that Gates is the major funder of an outlandish proposal to tackle climate change, a Harvard-based project to spray chemicals into the sky that would dim the sun.

Nothing could go wrong with that, could it?

So yes, I’d like to know if these massively powerful people like Gates, Musk and Bezos have their internal shit (mostly) together before they start taking serious action to handle our external shit. After all, did any of us vote for these characters?

What Are Your Two Questions For Gates?

So that’s it, my justification for why I’d ask Gates those two questions. Was it enough to convince you they were good ones?

Now, I’m sure you can think of others that would be good to ask him. Maybe even better than mine. Sadly, none of us regular folks out here in social media land really do have a guy we only know as The Editor who can wake us up from discordant dreams about despondent dinosaurs to allow us access to powerful people like Gates.

Still, why not play along? Why not tell me in the comments what two questions you would ask Bill Gates and why? After all, maybe The Editor will be reading someday. One can dream, right?

Thanks for reading! If you like my writing, support me by sharing my stuff, buying me a coffee, connecting with me on Twitter or Facebook, by checking out my podcast, The B&P Realm Podcast, by reading my novel, “The Teacher and the Tree Man” (or by listening to it for free) or by joining my community on Patreon.